Continues from Part I

Put Books Aside: Geometry in Motion - Lines & Symmetry

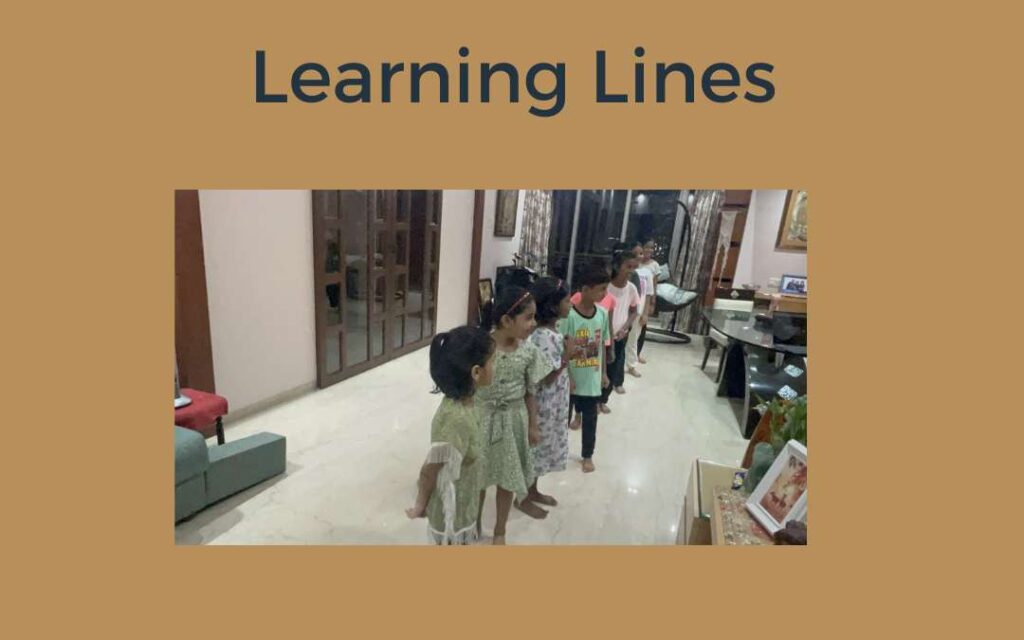

In dance I had already taught kids line formations both in column and or horizontal rows. Using this familiarity we explored the idea of parallel lines – movement taught them how these lines never converge. We experimented with angles in a variety of ways, positioning two palms for right angles, while simultaneously learning about perpendicular lines. Then we explored, experimented and moved a bit more – kids learnt to extend the line by each child extending their arms , bending the elbows to form acute and obtuse angles. A right angle wasn’t an abstract corner on a page; it was something they could feel in their shoulders.

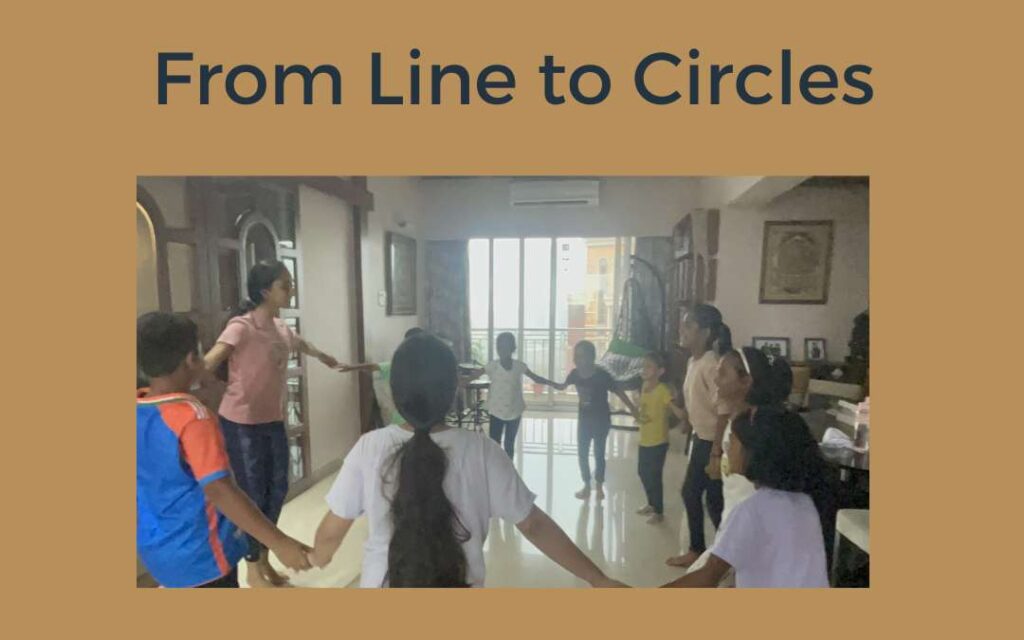

Learning about symmetry was easier than they had expected. I stood facing them and asked them to copy my movements exactly. When I raised my right arm, they instinctively raised their left. In pairs, one child became the leader and the other the mirror, adjusting movements to stay perfectly matched. Later, we worked as a group, forming symmetrical shapes around an imaginary centre line, checking whether both sides looked equal. By creating, breaking, and fixing symmetry through movement, they understood the concept through observation and play rather than definitions. It was far easier to experience symmetry than to explain it. Soon, they were creating their own movements and watching others mirror them, testing the idea from both sides.Without naming it yet, they had discovered mirror images.

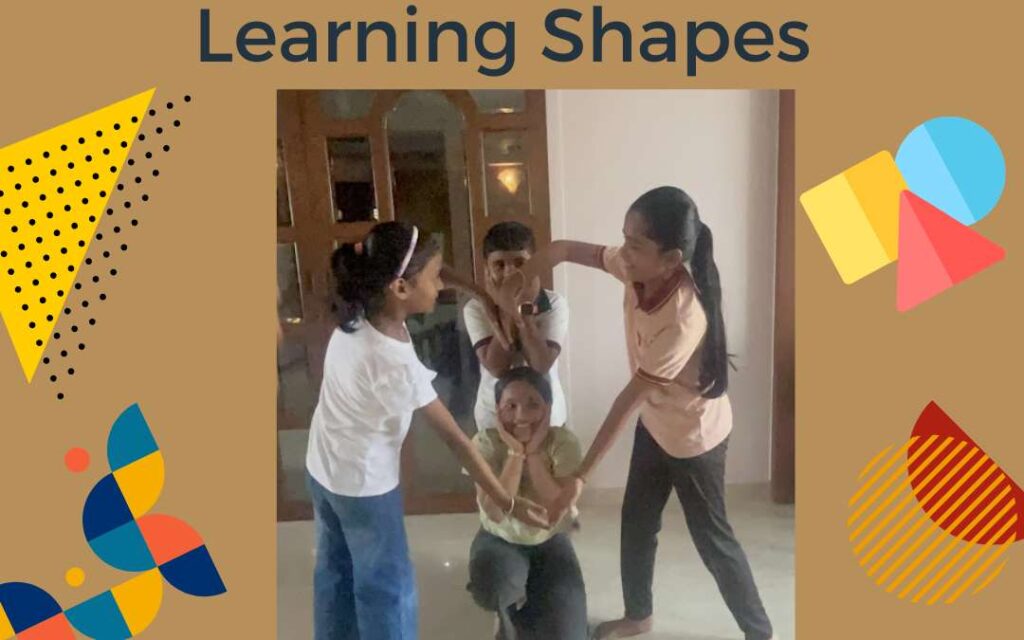

Similarly shapes were learnt.

Living Fractions

Fractions were a little more complex to break down, so we began with whole numbers. Standing tall represented one. From there, we introduced simple fractions like 2.5-two children standing and one kneeling-before gradually moving toward more complex values. We worked in teams, which made the learning collaborative rather than intimidating. Sometimes they solved the fractions individually, adjusting their own levels or limbs; other times they worked through group formations, negotiating who would rise, who would lower, and how the space should be shared.

Then we stepped it up. I arranged them in formations representing a fraction like 4.75 and asked them to rearrange themselves into another value-6 or 3.5. Without realising it, they were adding and subtracting fractions with their bodies and/ or group formations. Fractions stopped being abstract numbers and became something they could move, fix, and make equal together. What mattered was not precision, but participation. The children weren’t solving fractions; they were living them.

The use of formations and symmetry helped them understand equations visually: children either rearranged themselves from where they stood or crossed an imaginary central line to maintain balance. Thus they got unconsciously introduced to the concept of equations.

Clapping Time Into Understanding

Time signatures built directly on the way we had already learned numbers and fractions through the body. We started with four beats. I asked everyone to clap together, counting aloud: one, two, three, four. Each clap was equal, steady, and predictable. Once that felt secure, we moved to eight beats, keeping the same tempo but extending the count. They quickly realised that eight was simply two sets of four, just as they had doubled numbers earlier with bodies and levels. Then I pushed it further to sixteen beats, asking them to maintain the rhythm without speeding up or losing count. To make it concrete, I divided them into teams. One group clapped only on the first beat of every four, another clapped all four beats, and a third clapped for all sixteen. They could hear how smaller patterns fit neatly inside larger ones. Without ever using the word “division,” they understood how a bar could be broken into equal parts.

Add Your Heading Text Here

Art of Maths Through Science Of Dance/Movement

And so we went from topic to topic – not in a rigid manner but fluidly whatever logically and intuitively followed. None of this replaced formal mathematics, but something shifted for these kids – the way it had for me many years back – completing, shall we say, a full ‘circle’. Maths became their friend as they experienced in their bodies. What struck me most during those sessions wasn’t how quickly the children learned concepts, but how relaxed they became around them. Mathematics stopped being something that happened to them and became something they participated in.

Errors turned into adjustments, not failures. A formation that didn’t quite work was reworked, just like any step that felt awkward. That they took away that there are multiple ways to solve and errors could be fixed – hopefully would serve them well in life – an attitude , a skill that goes way beyond academics.

There’s a line often attributed to the mathematician William Thurston: we tend to think more effectively with spatial imagery on a larger scale. Dance expands that scale. It turns the classroom into a thinking space rather than a testing ground.

Cherry on the cake was that a few of them actually performed way beyond their own expectations in their exams. One day I hope to give this approach – making maths fun and then extending it to making learning fun a formal structure by integrating dance and movement – using Science of dance to teach art of maths.

My imagination runs wild at the thought of what if the teachers say put the books aside , push the desks aside , it is time to do mathematics – to begin with and then extending to many disciplines

How maths became fun continues part II of this article .

This article was originally published here.